written by Lauren

With the FIFA World Cup upon us and football fever raising temperatures globally (in the good sense), I thought it high time to revisit some of the greatest sports books ever written. As an American football fan, it’s my favorite sports season of the year. But November also saw the Houston Astros clinch baseball’s World Series, while the NBA is once again in full swing.

But you don’t have to be a sports fan to love sports books. There are sports tomes out there to satisfy every kind of reader—from the autobiography lover (I Am Zlatan Ibrahimovic) to the sociology-minded (Losers: Dispatches from the Other Side of the Scoreboard) to the feel-good story fans (Michael Lewis’ The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game).

I asked my friend and New York Times-bestselling author Matthew Goodman—whose own award-winning books include The City Game: Triumph, Scandal, and a Legendary Basketball Team and Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the World—to share his favorite sports books with ABC readers. Here they are:

The Boys of Summer by Roger Kahn

This is my all-time favorite sports book, in part because it’s not really a “sports book” at all. It’s structured in two parts: The first half is Kahn’s memoir of his time as a cub reporter covering the Brooklyn Dodgers during their heyday in the 1950s; in the second half of the book, he visits several of the club’s players years later, to discover what has become of them, in the days when major-league ballplayers were working-class heroes rather than the wealthy young celebrities of today. The Boys of Summer is a book, ultimately, about aging, loss, family, memory, and perhaps most of all about the ravages of time – how, as Shakespeare once wrote, “the whirligig of time brings in his revenges.”

Seabiscuit: An American Legend by Laura Hillenbrand

A Depression-era Cinderella tale, Seabiscuit intertwines the stories of three men who staked everything on the unlikeliest of horses and together helped him develop into an iconic champion: Seabiscuit’s owner, trainer, and jockey, each of whom was operating from a different set of motivations and each of whom became, for a time, a celebrity in his own right. With gorgeously vivid prose, sensitive characterizations, and an insider’s knowledge, and all the while setting a brisk pace that befits its eponymous hero, Laura Hillenbrand has masterfully recreated the colorful, idiosyncratic vanished world of American racetracks in the days when a horse could capture the popular imagination.

A Fan’s Notes by Frederick Exley

A Fan’s Notes is another sports book that is not really about sports at all – or, rather, is about far more than only sports. In this dark, moving, occasionally hilarious memoir-cum-novel, Frederick Exley recounts his time as an English teacher in a cold, isolated town in upstate New York in the 1950s; he’s lonely and depressed, mentally unstable, an alcoholic would-be writer full of unrealized ambitions, whose only meaningful hours arrive on Sunday afternoons, when he watches his beloved New York Giants play football. In the Giants’ handsome and talented star Frank Gifford (a former All-America at USC – a phenomenon that Exley memorably equates with being the Pope in the Vatican), Exley sees all that he wishes he might be, while recognizing that he is doomed never to be on the field, but only a fan watching from afar.

Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series by Eliot Asinof

The story of the Chicago “Black Sox,” the baseball players who took money from gamblers to lose the 1919 World Series, has long assumed the contours of a morality play: a tale of coarse, greedy ballplayers willing to sell out their team and their fans for a quick buck. In Eight Men Out Eliot Asinof admirably brings to light the human tragedy that lay beneath the newspaper headlines. Asinof describes White Sox owner Charles Comiskey as a “cheap, stingy tyrant” who paid his ballplayers far less than the going rate while wining and dining sportswriters to maintain their loyalty. In spirited, jaunty prose, Asinof brings the reader into a Runyonesque world of pool halls, hotels, and taverns, presenting a parade of colorful characters, none of them entirely on the level – perhaps most memorable among them Arnold Rothstein, mastermind of the fix, who “recognized the corruption in American society and made it his own.”

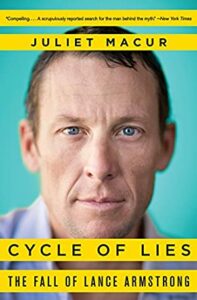

Cycle of Lies: The Fall of Lance Armstrong by Juliet Macur

A New York Times reporter who covered bicycle racing for years, Juliet Macur was the ideal writer to chart a rise and fall unparalleled in American sports history. The portrait of Lance Armstrong in Cycle of Lies is lucid and unsparing, with a novelistic complexity: He was an extraordinary athlete, willing to suffer for greatness almost beyond comprehension, but he was also angry, vain, greedy, and deeply dishonest. In his career he won seven consecutive Tour de France titles, at least in part thanks to abundant use of the banned drug EPO. Armstrong himself fervently denied doping, and when he conquered metastatic testicular cancer, Macur writes, “he had risen from his deathbed to a secular sainthood,” with a lucrative Nike line and a second career as the founder of the Livestrong Foundation. Eventually, of course, the truth came out and Armstrong was forced to admit that he had cheated. The empire quickly crumbled, and Macur ends her book with a memorable image: Armstrong, now broke and discredited, packing up and moving out of his Texas mansion.