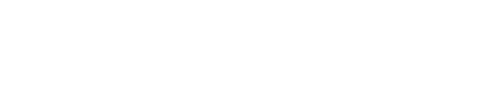

Kokoro—”the heart of things”—is the work of one of Japan’s most popular authors. This thought-provoking trilogy of stories explores the very essence of loneliness and stands as a stirring introduction to modern Japanese literature.

What is love, and what is friendship? What is the extent of our responsibility to ourselves and to others? A trilogy of stories that explores the very essence of loneliness, Kokoro opens with “Sensei and I,” in which the narrator recounts his relationship with an intellectual who dwells in isolation but maintains a sophisticated worldview. “My Parents and I” brings the reader into the narrator’s family circle, and “Sensei and His Testament” features the eponymous character’s explanation of how he came to live a life of solitude.

Natsume Soseki (1867–1916), perhaps the greatest novelist of the Meiji period, remains one of Japan’s most widely read authors. He wrote this novel in 1914, at the peak of his career, and it remains an excellent introduction to modern Japanese literature.

By Mike

Kokoro is a classic. The story is simple: a university student strikes up an unlikely friendship with a reclusive man he refers to as Sensei (master/teacher), over whom looms a large shadow of the past. Japan is rooted in centuries-old norms of respect, community and gender roles, and this book places characters right at the end of the Meiji era, which involved sudden and rapid modernization.

As I once dated a Japanese woman, who is a bestie still, and having practiced Japanese martial arts for years on end, I have built an affinity for Japan’s culture and history.

So when one of my hypercritical colleagues mentioned this as one of his favorite books and gifted me a copy, I read it as fast as I could. By which I mean this is one of the slowest books I’ve read in a while, and I’m a very slow reader—mind you, I’m so slow, at times pages have turned backwards. But in this case there’s an inexplicable subdermal suspense that immediately grabbed me and kept me engaged through what are mostly psychological musings.

Soseki is also known for the rumor-turned-legend in which he corrected one of his English lit students who attempted to literally translate the phrase “I love you.” Instead, Natsume told the student that it could only be expressed in Japanese as “it’s a beautiful moon,” which would cover all the necessary nightly, romantic context and subtext as is typical of the language.

As my friend once explained to me during our romance, when some things remained unspoken that were better said, “Kotodama” is a very important concept in Japan. This “spirit of words”—a belief that words hold mystical powers—is treated with the utmost care, which can border on reluctance and, for some, flat-out fear.

Kotodama is as much an unspoken theme in this book as the eponymous Kokoro—”the spirit of the heart/intention.” The book’s main character describes many, many emotions and thoughts, both perceived and experienced, albeit vaguely, and mostly these are things that remain unexpressed or addressed very formally or indirectly. It is often suggested that things remain unspoken as not to break custom, not to offend or simply to adhere to age-old gender norms.

All this is funneled into a curiosity about Sensei’s conflicting existential disposition and behavior and is continuously fueled in both the reader and the main character. And then the third act suddenly becomes a frame story about Sensei and serves as an emotional pay-off that really lingers for me.

Kotodama, Kokoro and existentialism are the themes most ascribed to this book, but as mental illness was once a thread weaving through my life, I dare say from what I’ve read online, it is overlooked how much this book has to say about emotional repression in Japan and the mental health, or rather, the decay of it, in men both young and old.

Trigger warning: themes of depression and suicide.