by Mike

The Last Voyage Of The Demeter, Nosferatu (Robert Eggers), Sinners, Dracula (Luc Besson), all in the span of a year or two. My best friend’s favorite book is what started it all, and as I actually write this we are discussing how and why it is the most adapted book ever (together with Sherlock Holmes, at least in the West) and why it works the way that it does.

This is not so much a review of a classic as much as an examination of why it is so often adapted and why there is a big Dracula inspired film release every few decades (allegedly followed by a real life economical recession, as someone on the interwebs surmised, take that as you will) and how the story might translate to the current zeitgeist.

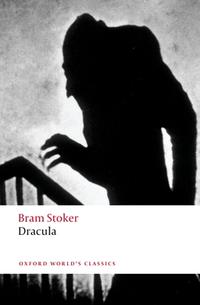

We discuss first of all that many, many iterations choose to put focus on Dracula himself, while we argue that the core strength of the book is the field of tension it spans by depicting the Count, well, actually very little. Throughout the book he is not so much a character as he is a pervasive force of (anti-?) nature, who is presented to us through the experience of characters that are his victims or people who are connected to them in one way or the other. The way the Count lurks around the edges of the narrative and only incidentally pops up for a bloody hello is really the core of why it is still such a foundation of the horror genre. He is mostly preluded or shrouded by (super)natural phenomena and it is strongly alluded that he is just as much a blood predator as a sexual predator, preying on the sexual obsessions and dated gender dynamics perpetuated by the Victorian era British male, Bram Stoker included (who was in fact an Irishman, mind you). Implicated danger, looming doom, and insidious gloom are the fabric of this one, and with which the most effective horror is still woven to this day. And, as research has proven: most people have sexual fantasies that involve dominating or being dominated (or worse) every once in a while, which might explain why the idea of a supernatural sexual predator might be ever so enthralling. Characters have often been used for spin-off books, if only to help us relive the vibe of the original. And films make much more money than books, so the shock value in returning to the silver screen in waves seems obviously logical.

So if we keep being compelled to retell it, how would a proper, modern-setting Dracula film or book justify its existence? As I understand it, purists say that the recent BBC mini-series miserably failed to do so. Our conclusion is that one of the ways could be to let Dracula himself remain the lurky-lurky thirsty-shady-ancient incel (isn’t he?) in the background, while his presence supernaturally amplifies the already rampant anxiety, depression, and sexual frustrations of this time. We argue that social media could play a major role or that generally internet-induced angst and dread might be a story device that could be leveraged to heighten the supernatural omens of the curse in the narrative. Sexual predators and discussions of how we’ve collectively permeated them are hyper relevant these days, and we would argue that an immortal white aristocratic dude from Victorian times would be a perfect antagonist in a modern story with sexuality and anxiety as horror devices. Maybe he could be met with (a metaphor for) the psychological measures we now teach more and more to our young men and women to stop rape culture from perpetuating itself. How the ever sexy hype around the blood drinking undead could be unmasked as a perpetuation of rape-culture while still catering to a new, younger audience might then be the crux to make a contemporary version that acknowledges the human urges from which it all stems without disregarding the sexual revolution and the emancipation of women.