By Dr. Otto Bleker

In her second autobiographic volume, The Cost of Living, Deborah Levy brings into practice her new attitude towards the people she’s met, including a male colleague, who talked about his wife without mentioning her name. While he spoke with her, Levy thought: “She does not have a name. She is a wife.”

Once at a funeral, she stepped towards a man “who cried like a woman,” while everyone else was crying in more socially acceptable ways. She asked him if he and the man being buried had been lovers. He said yes, on and off for many years, but they had never risked making themselves vulnerable to each other.

When he asked Levy whether her marriage was shipwrecked, his own honesty allowed her to speak freely. After she had spoken for a while, he said: “It seems to me that you would be better off finding another way to live.” The man would become a lifelong friend.

During these times, she rented a shed in a large garden that enabled her to write in peace and sort through her boxes of journals. One of them became the beginning of her novel Hot Milk, while others recorded meeting playwright David Gale and her certainty that they were fated for each other. They married in 1997, had two children together and were divorced by the time Levy turned 50-years-old.

Levy is at her best in middle-age, writing daily, keen to remark on the state of the patriarchate from personal experience. At a party, a tall, silver-haired man spoke with her about his military biographies and his unwell wife (no name) at home. He did not ask Levy one single question, not even her name.

Later, she thinks that “it is so mysterious to want to suppress women. It is even more mysterious when women want to suppress women. I can only think we are so very powerful that we need to be suppressed all the time. Anyway, like James Baldwin (Nobody Knows My Name) had taught me, I had to decide who I was and then convince everyone at the party that was who I was, but unfortunately in this phase, I was whistling in the dark.”

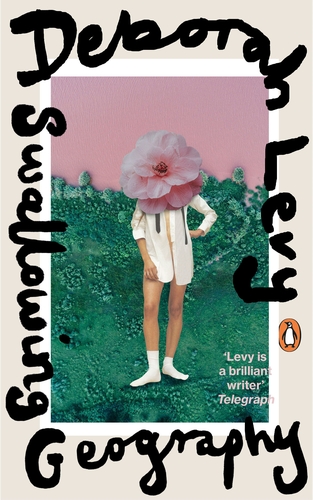

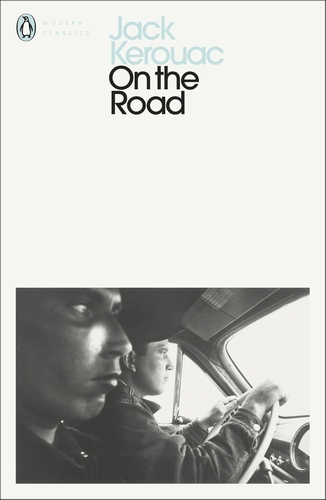

Already a keen observer of relationships between the sexes, Swallowing Geography was first published with other early writings in 1993. It was inspired by Jack Kerouac’s On the Road; the major woman character is named J.K. and experiences a wild journey, even broader in geography and time compared to On the Road’s protagonist. Concerning the phase of sexual arousal, she writes that people should learn “to speak by their fingertips”—a sentence we did not find in Kerouac’s original that makes clear her personal experience and growing knowledge in this field.

Levy writes that “to separate from love is to live a risk-free life,” and “to live without love, is a waste of time.” Levy acknowledged not to be Simone de Beauvoir, after all. No, she had gotten off the train at a different stop (marriage) and stepped on to a different platform (children).

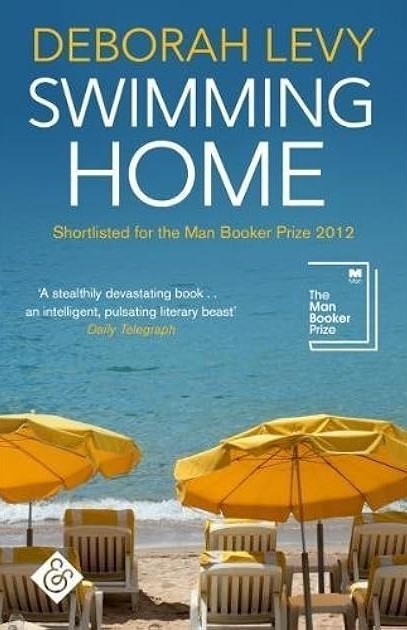

During her time in her first shed, she completed two novels: 2011’s Swimming Home and Hot Milk. It is clear she wrote Swimming Home, wherein two families rent a villa in the hills above Nice, with abundant pleasure. She explores how a powerful person can be vulnerable and a fragile person immensely powerful. Of its writing, she’s said that a writer builds for her readers a trail of breadcrumbs in the forest.

In Hot Milk, 64-year-old Rose divorces a Greek man while her daughter Sofia, age 25, gives up her academic studies to care for her. Despite her sacrifices, Sofia experiences the best weeks of her life, riding a car without a license, swimming topless in the sea and making love to both men and women.

This black medical comedy set in a white environment, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2016, continues Levy’s exploration of interior life and shares similarities with its predecessor (also shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2012) Swimming Home: its Mediterranean setting and explorations of sexuality and familial relationships.

And like all of her books, Hot Milk delves into ideas of womanhood and feminine power.