Written by Lynn

Written by Lynn

I arrived in Amsterdam in 1972 with some history in the American women’s liberation movement, had even started an organization for equal pay back in the day, and sometimes collaborated with the gay liberation activists. But living my perception of a liberated life in a foreign culture was a challenge! ABC was a playground for testing the difference between theory and practice as far as gender equality.

We could do that because Mitch, our boss, was an innovative gay guy who didn’t care about gender role models. Several colleagues were also gay men, not used to pushing women around. Everybody vacuumed the shop at the end of the day, everybody who wanted coffee was expected to make it themselves (also for others), and if Nancy and I wanted to test our mettle by hoisting new boxes of books through the second floor window with a rope and pulley instead of assuming that the guys would do it, Mitch said: “Go for it.”

We women found ourselves in a new culture, progressive and tolerant in many ways but conventional and unthinking in others. Some experiences seemed, from my American feminist perspective, odd to say the least.

Dutch male visitors like workmen expected a cup of coffee when entering the office but were surprised when we pointed at the pot and suggested heartily that they help themselves. Apparently, a cup of coffee not delivered by a female hand was not a real cup. (This was probably due to American versus Dutch hospitality customs, but at that stage in my life, I was framing many things as male versus female.)

Perplexing also was their pride in kitchen ineptitude. “I wouldn’t know how to make a cup of coffee!” or “I couldn’t fry an egg on my own.” Coming from the US Midwest, where self-reliance was a virtue, I couldn’t understand anyone bragging about what they couldn’t do and found it curious that they didn’t seem to want to learn at all.

I guess the underlying message was that there was no need to learn household chores because someone else was taking care of them, and, in honesty, she was honored for doing it.

The role of Mother-the-Wife at that time seemed greatly esteemed – echoes of the matriarchal position of queens? The Queen was venerated. Ambitious women of childbearing age seemed to be put down as if wanting to be both mother and professional was an affront to Our Queen. The Mother Role was deemed so important, that wanting a career was seen as settling for less than what one could be. “Why would you want to be a notary when you could be a mother?”

A couple other examples of cultural gender shock:

During the early ‘70s, I was the person who made daily deposits at the bank on the corner, so the manager knew me and found me rather strange but nice. (I brought in cakes one day for all the staff, just to be friendly, and he looked at me suspiciously, growled, “What do you want?”)

Just before Avo and I got married, he told me he’d done me a favor and already changed the last name on my bank account to Avo’s. He expected praise. Instead, I told him, “Well, Avo and I decided that I wouldn’t take his name and he wouldn’t take mine.” He changed it back but felt chagrined. And I felt bad that he was chagrined but also disappointed that he hadn’t asked if I would like his gesture.

The women students in the dorm where Avo lived were all surprised when we announced we were getting married. To me they said: “But I thought you liked your job!” These were female Masters students who couldn’t imagine I would want to be a married working woman… which made me wonder what they all were doing spending seven years of their lives studying if they primarily wanted to get married and not use their professional skills. Looking for the right guy, I guess, but that was never said. Perhaps it was assumed?

This was a culture shock for me. Raised with farm families where men and women worked hard, raised kids and ran the farm business together, I knew that work roles were usually set according to gender, but that men and women backed each other up to do the needful, took pride in being capable.

It didn’t take a penis to drive the tractor in harvest season when the crop had to be brought in over the next 24 hours. They took turns driving through the night. Nor did dads forget how to iron after learning it in the army. Certain gender roles were usual and preferred, but people did what had to be done. We learned it as children – when apples all fell from the tree due to a windstorm, every kid was given a paring knife and a place at the table and we all peeled and chopped till the job was done, boys and girls laughing and working together.

My sis ter Rachel helped run the bookstore business in the early ‘80s. She recalls a meeting we had at a distribution center. We were exploring the possibility of having our incoming books divided and protected with magnetic strips offsite and delivered to the four stores we managed at the time.

ter Rachel helped run the bookstore business in the early ‘80s. She recalls a meeting we had at a distribution center. We were exploring the possibility of having our incoming books divided and protected with magnetic strips offsite and delivered to the four stores we managed at the time.

The Manager we met was clearly unused to talking business with females, although he did his best…but Rachel says he blew it when he pointed to his assembly line, puffed out his chest and exclaimed: “Packing work is women’s work!” (I thought he was praising their dexterity; Rachel found his statement denigrating. Perhaps our different reactions are another case of confusing culture with gender differences?) We hustled out of there and figured out another method.

Although International Women’s Day has been celebrated on March 8 since the late ‘70s, I ‘ve never known what to do on that specific day, which can feel like a forced premature celebration of a tribe still finding its cohesion. And in fact, I feel most comfortable in gatherings with both men and women.

Since the liberation movements of the ‘70s, people have reconsidered traditional roles. “Normal” now has many variations, but also increasing backlash. Women, men, everybody should be free to be our best selves. We need everyone to shine, free to weigh up and recalibrate outside expectations and to make our own arrangements with partners and co-workers and co-parents.

But we’re not yet there, so I’m confused about what to do on March 8. Until patriarchy wanes and femicide is archaic, there’s work to be done.

But we’re not yet there, so I’m confused about what to do on March 8. Until patriarchy wanes and femicide is archaic, there’s work to be done.

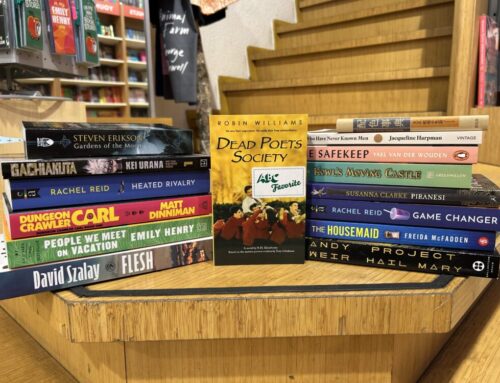

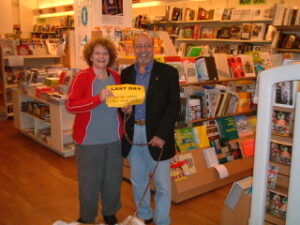

In the meantime, I do enjoy the company of people who are professional and caring, who take time to eat and laugh together while just getting on with it. I learned this at the kitchen table and have tried to model it at ABC. How? By hiring persons, not labels, and by offering a smorgasbord of books that appeal to all sorts of individuals. Working the cash register, I’m always surprised to see the variety of books our customers buy. Letting a hundred flowers bloom, a hundred modes of thought (and lifestyle) prevail has been an ABC founding principle, one which continues to this day.