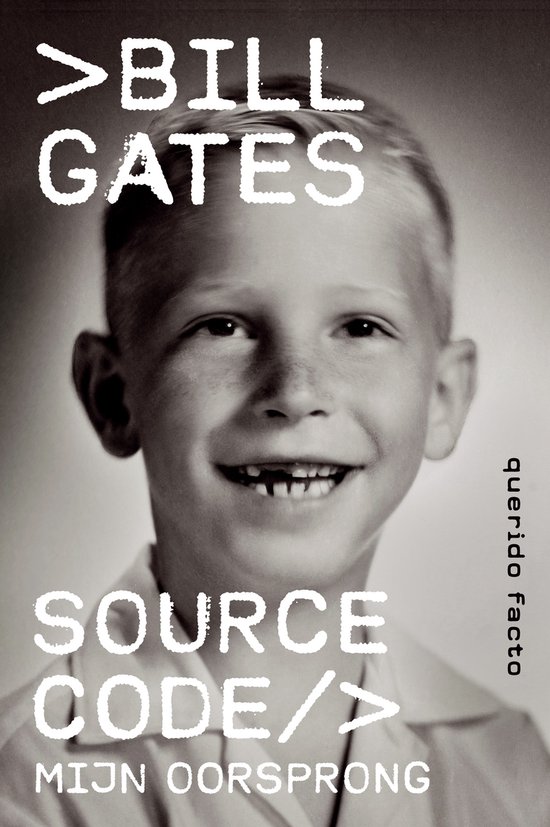

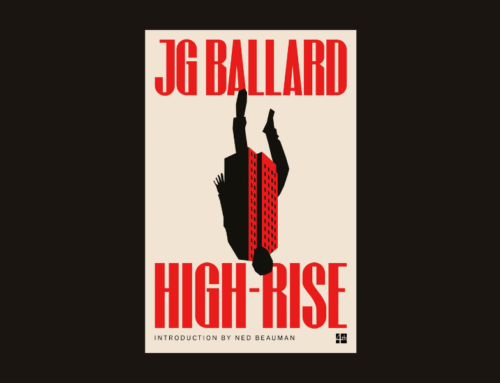

Source Code is not about Microsoft or the Gates Foundation or the future of technology. It’s the human, personal story of how Bill Gates became who he is today: his childhood, his early passions and pursuits. It’s the story of his principled grandmother and ambitious parents, his first deep friendships and the sudden death of his best friend; of his struggles to fit in and his discovery of a world of coding and computers in the dawn of a new era; of embarking in his early teens on a path that took him from midnight escapades at a nearby computer center to his college dorm room, where he sparked a revolution that would change the world.

Bill Gates tells this, his own story, for the first time: wise, warm, revealing, it’s a fascinating portrait of an American life.

By Lynn

Bill Gates tells his origin story growing up in Seattle with loving, supportive parents in a flowing style. This first part of his autobiographical tale ends just as Microsoft is getting started as a company, so this book takes place from 1955– 1978. As he leads the reader through these familiar decades, a certain nostalgia for the openness of that time arose. (This happens with older people like this reviewer, whose recollections of how things were back then before personal computers and internet are met with blank stares – just as she responded to all the old peoples’ wanderings down memory lane as a kid.) So I’m grateful to the author for the effort he took to describe the formative effects of growing up with freedom to roam and take risks, with teachers and parents who challenged kids at all levels, who valued reading and card playing and civic responsibility. This history felt familiar to the life I knew from the 1950’s and ‘60s.

Trey, as he was called, was an inquisitive kid. His closing sentence is “In many ways I’m still that eight-year-old sitting at Gami’s dining room table as she deals the cards. I feel the same sense of anticipation, a kid alert and wanting to make sense of it all.”

Gami always won at cards. Trey realized that she was keeping track of the cards played by others; she had a stoic, mental discipline he admired and developed to his advantage, especially in college. His natural math ability became a wild card to enjoy broadly all the courses that interested him; the discipline need to skip required classes and only cram for the final exam to get the needed grade was developed early. His extreme focus and ability to forge on without sleep were instrumental in writing computer code from scratch – first in his head, then on yellow legal pads, then finally on a shared computer.

An unexpected treat emerged in the pages describing his years at Harvard, a ”six degrees of separation” connecting the author with ABC. The story goes like this:

During the early years of the bookshop, then called American Discount Book Center, Baltimore friends of co-founder Sam Boltansky would ask him to let their teenage kids be summer interns at the bookshop, living upstairs in Amsterdam. Although we’ve lost touch with most of them, we know that a major stockbroker, a Broadway entertainment lawyer, the co-founder of an important law firm – all came to us through this informal program as youngsters. One of them was Andy, the son of Sam’s lawyer, who was so smart that his also very smart parents didn’t know what to do with him the summer before he was to enter Harvard at age 16. Sam said he could come to Amsterdam to intern in the bookstore for the summer and so he did. Andy was (is?) a math savant who found putting books in alphabetical order extremely challenging when it came to the MacAvoy, McClelland, MacMurty names. Where was the system? “Andy, there is no system. Just put them where people can find them,” was my answer. That a system could be loosely based and flexible was a mental challenge. But as he got his beer legs, Andy became more confident and shared his sense of humor. He was an ace at Tric Trac, something we didn’t know when inviting him to a sociable tric trac tournament which was taken more seriously by some players than others. We all had yellow tee shirts inked with “Tric Trac 1973” in white acrylic letters. Andy nonchalantly wiped the floor with all of us, accepting his title with an “aw shucks” manner that completely agonized the defending Dutch champion. I hope he has fond memories of that Saturday evening in Amsterdam.

We lost track of Andy, even Sam didn’t know what had happened to him after Harvard excepting that he’d joined a prestigious Wall Street law firm and was working all the time. His parents died young and I haven’t been to Baltimore in decades. But here in Bill Gates’ early autobiography, up pops Andy as a classmate in Math 55, where a bunch of five very advanced math students traveled and studied as a pack. They all became friends, and Andy and Bill roomed together the following year. Both left the math program – Andy to law, Bill to computers, although there was no academic course for credit at that time. He and boyhood friend Paul Allen wanted to build a company together, putting a PC in every home loaded with their software. They did.

Here’s what Andy Braiterman says about Bill:

More info on Andy now here and on The Harvard Gazette.

Curious about Gate’s next autobiographical book, I take away from the first an enjoyable weekend read and reminder of a shared hero, Richard P. Feynman, who said “The prize is the pleasure of finding the thing out.”

Curiosity feeds imagination feeds creation feeds knowledge feeds curiosity, and what a joy to be able to follow this path in one’s life, starting early.