By Lynn

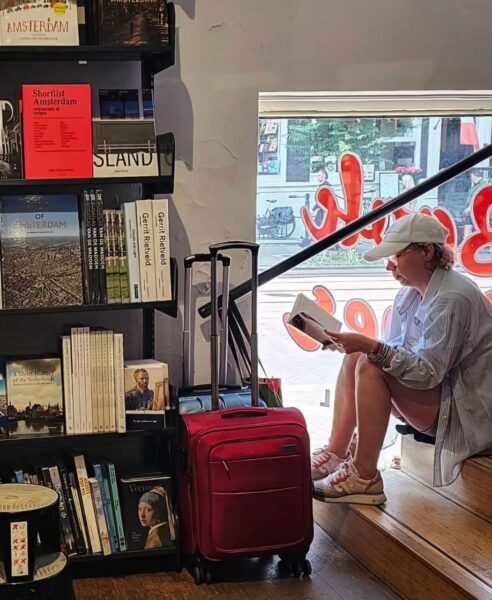

“While we do not take official stances against any political alignment, we feel the need to acknowledge the situation and to live up to our own values of Fundamental Human Rights, Democratic Principles, Openness, Inclusivity and Respect. We do this through our collection of books. No more, no less. This collection is created and curated by our buyers in response to demand from our customers.

We anchor ourselves in what we do best: creating a safe and welcoming place where stories and ideas come alive. Our mission is as vital today as it has ever been.”

Publishing used to be done by printers who bore the risk between author and sales success, often selling the books right out of the print shop. Later, publishing was often done by intellectuals, a gentleman’s trade, who contracted the printing out to a printer but warehoused and distributed their own book stocks. Sales were handled by others.

In 1972, there were at least 40 English language paperback publishers to order from.

In 1972, there were at least 40 English language paperback publishers to order from.

More recently, English language publishers have consolidated to just five big companies with teams that straddle the Atlantic.

Why does this matter to the reader?

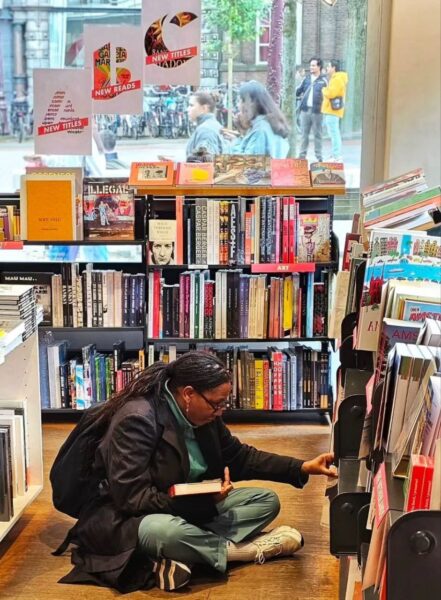

Because in these times of political upheaval, corporate publishers are beholden to very sensitive financial markets. Publishers will necessarily be inclined to self-censure their acquisitions rather than risk upsetting the market with controversial material, feeding readers content poor in nutrients. Readers may become anemic, without even knowing what they’re missing.

When the Big Five publishers cancel contracts and shy away from bringing divisive new titles into being, we will need to rely more and more on books already written and those made by smaller independent publishers, like Oneworld Publications, whose author Paul Lynch won the Booker Prize in 2023 for Prophet Song. This Mom-and-Pop house also published the 2015 and 2016 Booker Prize winners.

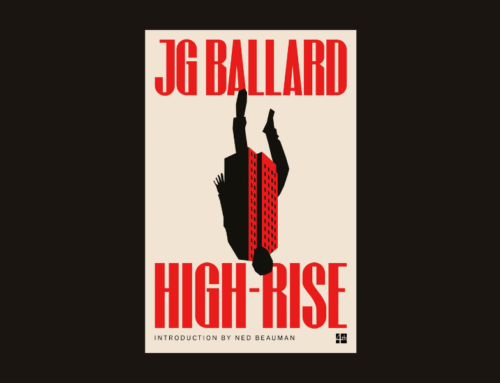

Faber is an independent publishing house with its own writing academy. They support and help develop quality writing. There are still small and midsize independent publishers who are less dependent on the financial markets in their selection of which titles to publish, but they are increasingly at risk.

As quirky booksellers, we hope that other sources will give us broad choices and surprising voices to keep us warm in the chilly times that seem to be coming.